Pure and partial functions

In the first chapter we've seen an informal definition of a pure function:

A pure function is a procedure that given the same input always returns the same output and does not have any observable side effect.

Such an informal statement could leave space for some doubts, such as:

- what is a "side effect"?

- what does it means "observable"?

- what does it mean "same"?

Let's see a formal definition of the concept of a function.

Note. If X and Y are sets, then with X × Y we indicate their cartesian product, meaning the set

X × Y = { (x, y) | x ∈ X, y ∈ Y }

The following definition was given a century ago:

Definition. A _function: f: X ⟶ Y is a subset of X × Y such as

for every x ∈ X there's exactly one y ∈ Y such that (x, y) ∈ f.

The set X is called the domain of f, Y is it's codomain.

Example

The function double: Nat ⟶ Nat is the subset of the cartesian product Nat × Nat given by { (1, 2), (2, 4), (3, 6), ...}.

In TypeScript we could define f as

const f: Record<number, number> = {

1: 2,

2: 4,

3: 6

...

}

The one in the example is called an extensional definition of a function, meaning we enumerate one by one each of the elements of its domain and for each one of them we point the corresponding codomain element.

Naturally, when such a set is infinite this proves to be problematic. We can't list the entire domain and codomain of all functions.

We can get around this issue by introducing the one that is called intensional definition, meaning that we express a condition that has to hold for every couple (x, y) ∈ f meaning y = x * 2.

This the familiar form in which we write the double function and its definition in TypeScript:

const double = (x: number): number => x * 2

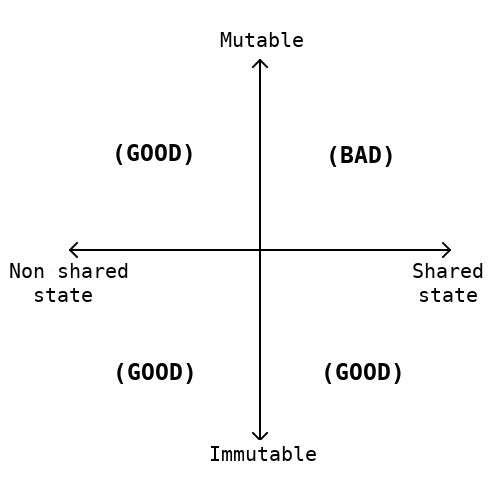

The definition of a function as a subset of a cartesian product shows how in mathematics every function is pure: there is no action, no state mutation or elements being modified. In functional programming the implementation of functions has to follow as much as possible this ideal model.

Quiz. Which of the following procedures are pure functions?

const coefficient1 = 2

export const f1 = (n: number) => n * coefficient1

// ------------------------------------------------------

let coefficient2 = 2

export const f2 = (n: number) => n * coefficient2++

// ------------------------------------------------------

let coefficient3 = 2

export const f3 = (n: number) => n * coefficient3

// ------------------------------------------------------

export const f4 = (n: number) => {

const out = n * 2

console.log(out)

return out

}

// ------------------------------------------------------

interface User {

readonly id: number

readonly name: string

}

export declare const f5: (id: number) => Promise<User>

// ------------------------------------------------------

import * as fs from 'fs'

export const f6 = (path: string): string =>

fs.readFileSync(path, { encoding: 'utf8' })

// ------------------------------------------------------

export const f7 = (

path: string,

callback: (err: Error | null, data: string) => void

): void => fs.readFile(path, { encoding: 'utf8' }, callback)

The fact that a function is pure does not imply automatically a ban on local mutability as long as it doesn't leaks out of its scope.

Example (Implementazion details of the concatAll function for monoids)

import { Monoid } from 'fp-ts/Monoid'

const concatAll = <A>(M: Monoid<A>) => (as: ReadonlyArray<A>): A => {

let out: A = M.empty // <= local mutability

for (const a of as) {

out = M.concat(out, a)

}

return out

}

The ultimate goal is to guarantee: referential transparency.

The contract we sign with a user of our APIs is defined by the APIs signature:

declare const concatAll: <A>(M: Monoid<A>) => (as: ReadonlyArray<A>) => A

and by the promise of respecting referential transparency. The technical details of how the function is implemented are not relevant, thus there is maximum freedom implementation-wise.

Thus, how do we define a "side effect"? Simply by negating referential transparency:

An expression contains "side effects" if it doesn't benefit from referential transparency

Not only functions are a perfect example of one of the two pillars of functional programming, referential transparency, but they're also examples of the second pillar: composition.

Functions compose:

Definition. Given f: Y ⟶ Z and g: X ⟶ Y two functions, then the function h: X ⟶ Z defined by:

h(x) = f(g(x))

is called composition of f and g and is written h = f ∘ g

Please note that in order for f and g to combine, the domain of f has to be included in the codomain of g.

Definition. A function is said to be partial if it is not defined for each value of its domain.

Vice versa, a function defined for all values of its domain is said to be total

Example

f(x) = 1 / x

The function f: number ⟶ number is not defined for x = 0.

Example

// Get the first element of a `ReadonlyArray`

declare const head: <A>(as: ReadonlyArray<A>) => A

Quiz. Why is the head function partial?

Quiz. Is JSON.parse a total function?

parse: (text: string, reviver?: (this: any, key: string, value: any) => any) =>

any

Quiz. Is JSON.stringify a total function?

stringify: (

value: any,

replacer?: (this: any, key: string, value: any) => any,

space?: string | number

) => string

In functional programming there is a tendency to only define pure and total functions. From now on with the term function we'll be specifically referring to "pure and total function". So what do we do when we have a partial function in our applications?

A partial function f: X ⟶ Y can always be "brought back" to a total one by adding a special value, let's call it None, to the codomain and by assigning it to the output of f for every value of X where the function is not defined.

f': X ⟶ Y ∪ None

Let's call it Option(Y) = Y ∪ None.

f': X ⟶ Option(Y)

In functional programming the tendency is to define only pure and and total functions.

Is it possible to define Option in TypeScript? In the following chapters we'll see how to do it.